Leonardo da Vinci

Walter Isaacson is a historian and journalist best known for writing biographies of important public figures, including Henry Kissinger, Benjamin Franklin, Albert Einstein, Steve Jobs, Jennifer Doudna, and Elon Musk.

One of the best books which I like the most is Leonardo da Vinci.1 A thick 600-page book based on thousands of pages from Leonardo’s astonishing notebooks and new discoveries about his life and work, Walter Isaacson tells the story of how Leonardo da Vinci connected his art to his science.

“Study the science of art. Study the art of science. Develop your senses—especially learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else.”

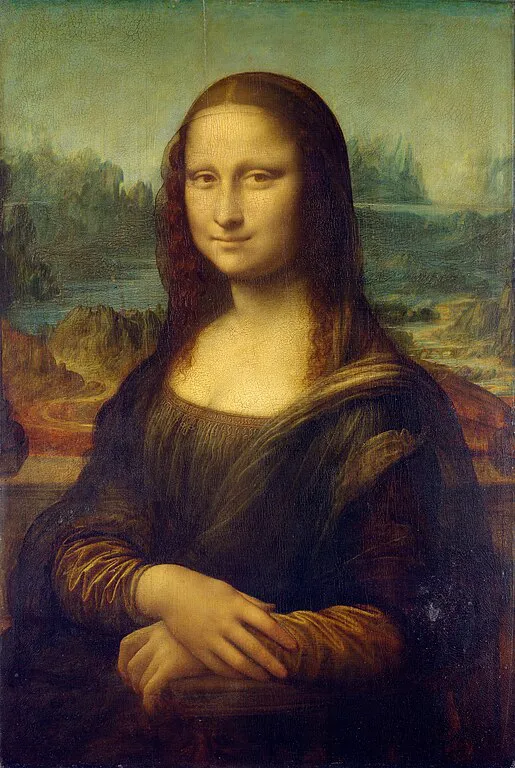

Among his many other brilliant works, Leonardo da Vinci produced the two most famous paintings in history: The Last Supper2 and the Mona Lisa3. With a passion that sometimes became obsessive, he pursued innovative studies of anatomy, fossils, birds, the heart, flying machines, botany, geology, and weaponry. His ability to stand at the crossroads of the humanities and the sciences, made iconic by his drawing of Vitruvian Man, made him history’s most creative genius.

Leonardo started early as an apprentice in the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio in Florence, where he was exposed to a wide array of disciplines, including painting, sculpture, and mechanical arts.

His early exposure to various fields shaped Leonardo’s broad interests. He soon surpassed his contemporaries with his incredible ability to observe the world around him and translate those observations into art and designs. The meticulous precision with which he approached painting, coupled with his scientific curiosity, laid the groundwork for his later masterpieces.

Painted between 1495 and 1498, The Last Supper is a large mural depicting the moment Jesus Christ announces that one of his disciples will betray him. Leonardo demonstrates his mastery of perspective, light, and human emotion. The twelve apostles are arranged in groups of three, and each character reacts differently to Christ’s revelation, giving the painting a sense of drama and psychological depth.

However, The Last Supper was painted using an experimental technique—tempera on a dry plaster wall—which made it highly susceptible to damage. Over the centuries, the painting has deteriorated significantly, requiring multiple restoration efforts. It is one of the most studied and revered works in art history.

Mona Lisa, painted between 1503 and 1506, is a portrait of Lisa Gherardini, the wife of a wealthy Florentine merchant, that has captivated viewers for centuries. Mona Lisa’s enigmatic smile, combined with Leonardo’s revolutionary use of Sfumato4 (blending colors and tones to create soft transitions), adds a layer of mystery and realism.

The Mona Lisa is a testament to Leonardo’s deep understanding of anatomy and his ability to observe subtle details in human expression. Her smile, which seems to change depending on the angle from which one views her, is just one of the many reasons why the painting has continued to intrigue viewers for over 500 years.

Leonardo constantly questioned the natural world. He was a prolific writer and sketcher, filling thousands of pages with ideas, observations, and inventions. He dissected human corpses to study the muscles, bones, and organs, making detailed sketches that were far ahead of his time. His drawings, such as The Vitruvian Man,5 a study of the proportions of the human body, are considered masterpieces of art and science.

Leonardo’s anatomical studies extended to the physiology of the body as well. He was fascinated by how the human body functioned, and his drawings of the human heart, for example, are incredibly accurate, anticipating modern anatomical discoveries. His research into the circulation of blood, muscle movement, and the brain was groundbreaking, although his findings were not published in his lifetime.

In 1994, Bill Gates purchased the Codex Leicester,6 a collection of scientific writings by Leonardo da Vinci, for US$30.8 million at an auction.

Leonardo’s notebooks are filled with designs for machines that, though never built in his time, foreshadowed future technological developments. He sketched ideas for flying machines, including an early version of a helicopter, a parachute, and even a tank. Unfortunately, these inventions were not feasible with the technology available in the 15th century.

Leonardo da Vinci exemplified the Renaissance ideal of a polymath—someone who is not bound by one discipline but seeks to understand the world in all its complexity.

-

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 1452 – 2 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested on his achievements as a painter, he has also become known for his notebooks, in which he made drawings and notes on a variety of subjects, including anatomy, astronomy, botany, cartography, painting, and palaeontology. Leonardo is widely regarded to have been a genius who epitomised the Renaissance humanist ideal, and his collective works comprise a contribution to later generations of artists. ↩

-

The Last Supper is a mural painting by Leonardo da Vinci, dated to c. 1495–1498, housed in the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy. The painting represents the scene of the Last Supper of Jesus with the Twelve Apostles, as it is told in the Gospel of John – specifically the moment after Jesus announces that one of his apostles will betray him. Its handling of space, mastery of perspective, treatment of motion and complex display of human emotion has made it one of the Western world’s most recognizable paintings and among Leonardo’s most celebrated works. Some commentators consider it pivotal in inaugurating the transition into what is now termed the High Renaissance. ↩

-

The Mona Lisa is a half-length portrait painting by Leonardo da Vinci. Considered an archetypal masterpiece of the Italian Renaissance, it has been described as “the best known, the most visited, the most written about, the most sung about, and the most parodied work of art in the world.” The painting’s novel qualities include the subject’s enigmatic expression, monumentality of the composition, the subtle modelling of forms, and the atmospheric illusionism. ↩

-

Sfumato is a painting technique for softening the transition between colours, mimicking an area beyond what the human eye is focusing on, or the out-of-focus plane. It is one of the canonical painting modes of the Renaissance. Leonardo da Vinci was the most prominent practitioner of sfumato, based on his research in optics and human vision, and his experimentation with the camera obscura. He introduced it and implemented it in many of his works, including the Virgin of the Rocks and in his famous painting of the Mona Lisa. He described sfumato as “without lines or borders, in the manner of smoke.” ↩

-

The Vitruvian Man is a drawing by Leonardo da Vinci, dated to c. 1490. Inspired by the writings of the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius, the drawing depicts a nude man in two superimposed positions with his arms and legs apart and inscribed in both a circle and square. It was described by the art historian Carmen C. Bambach as “justly ranked among the all-time iconic images of Western civilization.” Although not the only known drawing of a man inspired by the writings of Vitruvius, the work is a unique synthesis of artistic and scientific ideals and often considered an archetypal representation of the High Renaissance. ↩

-

The Codex Leicester is a collection of scientific writings by Leonardo da Vinci. The codex is named after Thomas Coke, Earl of Leicester, who purchased it in 1717. The codex provides an insight into the mind of the Renaissance artist, scientist and thinker, as well as an exceptional illustration of the link between art and science and the creativity of the scientific process. ↩