Algorithmic Age - Code Shaping Cognition and Society

An article popped up on Hacker News, Kill your Feeds - Stop letting algorithms dictate how you think, and instead of reading it right away; I got to the original video first (suggested by the comments in that discussion thread). This topic has been in my thoughts for a while and has been mentioned in conversations, suggesting ideas to be mindful of the over-algorithmic firehose of entertainment and information our way.

It is a normal routine for almost all of us to start our day with a Smartphone—starting our day with algorithms. We no longer read the news; the algorithm feeds us the relevant ones. We can even ask it to learn our habit and show us only the feel-good news in a certain geography on a specific topic or some topics.

As we started our commute to work, our favorite music streaming service crafted a playlist to suit our tastes while a navigation app optimized the route. As the day progressed, we barely made any unmediated choice and could even blissfully submit to the final hum of white noise that puts us to sleep.

In ways big and small, digital algorithms – the invisible computational rules behind our apps and platforms – quietly run the show of modern life. From the videos recommended on YouTube to the posts promoted on social media feeds, algorithms curate much of what we consume.

Of course, it does have a lot of good outcomes.

These automated decision systems bring undeniable benefits. They filter the overwhelming flood of information, connecting us with relevant content, products, and people in seconds. Algorithms help doctors diagnose diseases, enable cars to drive themselves, and route emergency services efficiently. In theory, this algorithmic optimization frees humans to make better decisions and enjoy personalized experiences.

“Succumbing to algorithmic complacency means you’re surrendering your agency in ways you may not realize,” warns Alec Watson.

Yet, as we increasingly outsource our attention and choices to machines, concerns are mounting that something profound is being lost or distorted.

More intelligent and curious people are beginning to realize that algorithms are not neutral tools; they carry the values and goals – and sometimes the biases – of those who design them. Many of today’s most influential algorithms are engineered to maximize engagement or profit, not to promote human flourishing.

Eventually, they produce unintended side effects: narrowing our perspectives, exploiting our psychological vulnerabilities, spreading falsehoods, eroding privacy, and entrenching social inequalities. If we let algorithms think for us in everything, we may be imperceptibly trading away our independence of mind.

Echo Chamber

Not long ago, information was a one-size-fits-all affair – everyone read more or less the same front-page news. Today, two people can open the same social media app and enter entirely different realities. If you “like” a tweet about climate change, your timeline might soon brim with environmental news; your neighbor’s feed tilts toward sports or finance based on what they engaged with. This personalization is convenient but comes at a cost: we each inhabit our own algorithmically curated bubble. Our existing beliefs are reinforced inside these digital echo chambers while dissenting views are filtered out.

Consider the experience of a normal individual, a moderate newsreader who clicked on a couple of videos about immigration on YouTube. The platform’s recommendation algorithm, designed to keep him watching, soon served up more sensational content. With each click, the “Up Next” suggestions grew a little more extreme in tone. Before long, the video feed had shifted from balanced newscasts to polemical rants echoing the same viewpoint. Unbeknownst to the individual, someone can be gently guided into an information silo – a feedback loop of content that amplified one side of a complex issue.

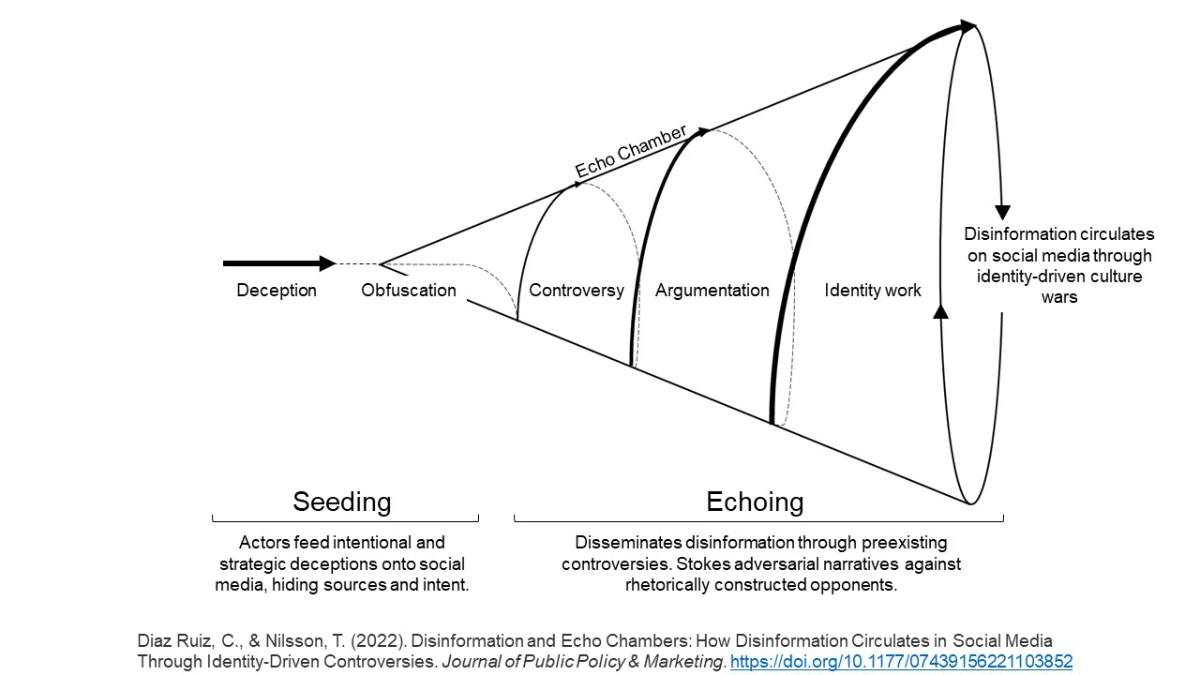

This phenomenon is popularly known as the filter bubble or echo chamber. It’s what happens when algorithms customize content to such a degree that we mainly hear our opinions thrown back at us. Social media is especially notorious for this. One study of Facebook found that users are far more likely to see news that aligns with their political ideology than news that challenges it.

The researchers estimated that a liberal Facebook user’s exposure to conservative content was only about 24%, and vice versa, only 35% of what it would be in a non-algorithmic feed. Over time, that creates fertile ground for confirmation bias – we interpret new information to confirm what we already think because that’s mostly all we encounter.

There are always debates about how severe these algorithmic echo chambers really are. Some studies suggest many people still seek out diverse sources, and not everyone is trapped in a bubble online. Nevertheless, evidence shows that highly personalized feeds can insulate us from alternative viewpoints. An environment where one’s beliefs are constantly reinforced with little challenge may breed greater social and political polarization. It’s easy to see how: if your feed portrays the world as overwhelmingly agreeing with your stance, the other side can start to seem wrong, irrational, or even dangerous. Nuance and common ground evaporate.

The vicious cycle often goes unnoticed by the user. Like a frog in boiling water, we acclimate to our echo chamber. Each incremental tweak of the algorithm further hones what we see in ways we hardly perceive. Over months and years, one’s worldview can skew considerably. A person who once consumed a mix of moderate and fringe content might, through countless micro-reinforcements, view the fringe as mainstream.

The echo chamber effect not only reinforces biases but also fosters tribalism. Online communities splinter into insular groups – left, right, pro-this, anti-that – each with its own self-confirming narrative. Empathy for other perspectives wanes when you rarely encounter them except as caricatures. Sometimes, the algorithm recommends increasingly radical groups or content as it “learns” what fires up a user. It’s no coincidence that periods of growing polarization in politics and society have coincided with the rise of algorithm-driven news feeds. Studies have linked social media echo chambers to spikes in polarization and even the spread of extremism.

It’s important to note that technology is not solely to blame; human nature plays a significant role. We like hearing things that validate our feelings. Algorithms, however, fuel that fire by feeding us a steady diet of validation. The neotribalism of the internet age – fragmented communities clustering around shared identities or beliefs – is amplified by recommendation engines that cluster similar people together.

Once in a tribe, social dynamics encourage us to double down on group orthodoxy. Sensing our continued engagement, the algorithm obliges with more of the same, completing the circle. There are, however, potential remedies. Some platforms have introduced features to break the echo chamber, such as exposure to opposing viewpoints or prompts like “See content from other perspectives.” However, these measures are voluntary and not widely used. Other ideas include algorithmic transparency, where users could understand and adjust the criteria that shape their feed – bursting their bubble. Until such solutions become common, the onus is mainly on individuals to seek out diversity. The first step is recognizing that if the information around you sounds like an echo, it might be time to widen your circle of sources.

Attention Economy

Every day, billions of people tap, scroll, and swipe through feeds honed by some of the most sophisticated algorithms ever devised. These feeds are engineered for a singular purpose: to capture and hold our attention. In the industry, it’s often said that in the attention economy, attention is the product – bought and sold by advertisers and fought over by tech companies. The result is an arms race to exploit psychological hooks that keep users glued to their screens. For many, this has led to compulsive usage patterns, frayed concentration, and rising anxiety in the constant hunt for the next notification buzz.

Designers of popular apps will candidly admit they borrow tricks from casinos. The infinite scroll of your social media timeline, the pull-to-refresh gesture that can spawn new content, the red badge alert signaling “something new” – these features create compulsion loops similar to a slot machine. You never know what post or image might come next; the unpredictability and novelty stimulate the brain’s reward circuitry with hits of dopamine. So we keep scrolling, refreshing, checking – long past the point of real interest. Algorithms learn which stimuli trigger us and then deploy those stimuli at the right intervals to maximize engagement. Over time, we may find our ability to focus waning, our moods more restless, shaped by the algorithm’s artificial rhythm rather than our own natural pace.

The toll on mental health is becoming increasingly apparent. Numerous studies have linked heavy social media use with feelings of loneliness, anxiety, and depression. Particularly among teens and young adults, who’ve never known a world without the algorithmic feed, rates of anxiety and depression have climbed in tandem with smartphone and social platform adoption. While correlation isn’t causation, the immersive design of these platforms is a prime suspect in what some call a mental health epidemic.

Even outside clinical diagnoses, many people report a fraying of their attention and increased stress. Scrolling through algorithm-curated feeds can induce a phenomenon popularly dubbed “doomscrolling.”1 This is when you feel compelled to keep consuming negative news or social media posts, even as they make you upset or worried. The algorithm doesn’t necessarily distinguish between positive engagement and outrage or fear; all it tracks is that you’re engaged. If polarizing or upsetting content keeps you hooked, you’ll get more. Thus, someone anxious about world events might be shown more alarming content, amplifying their distress. It’s a feedback loop where the user’s frazzled state generates the signals that tell the algorithm to serve up more of the same.

Another psychological vulnerability exploited by algorithms is our desire for social validation. Platforms like Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok quantify our social approval in likes, hearts, and view counts – metrics that algorithms use to sort and promote content. It’s all too easy to start deriving one’s self-worth from these numbers. A teenager might post a photo and then obsessively monitor how many likes it gets, comparing with peers. If the feedback falls short, feelings of inadequacy or exclusion can creep in. Conversely, a dopamine rush accompanies a post that “goes viral,” reinforcing the cycle of seeking external validation. The algorithm quietly reinforces this behavior by boosting content that quickly garners attention, effectively teaching users that provocative or extreme posts are rewarded with more visibility. The pressure to perform for the algorithm can distort one’s authentic voice and heighten social anxiety – a dynamic well-documented by psychologists studying social media’s impacts.

It’s not only youths who are affected. Adults, too, feel their concentration fragmented by the constant pings and the endless stream of algorithmically curated tidbits. Many find it increasingly difficult to read long-form content or engage in offline activities without the itch for digital distraction. Work productivity suffers when toggling between tasks and the lure of algorithmic feeds. At night, the screen’s blue glow and the mental churn of social comparison or information overload can disrupt sleep, contributing to a cycle of fatigue and stress. Yet, it’s worth noting the attention economy’s products are delightful by design. There’s a reason we find ourselves binge-watching recommended shows or scrolling TikTok for an hour that felt like minutes – the experience is often genuinely fun or at least diverting.

Algorithms can deliver moments of joy, humor, and connection (who hasn’t been delighted by a surprisingly perfect song suggestion or a reunion with an old friend in their feed?). This is the delicate balance: the very features that harm us in excess are also gratifying in moderation. The challenge is that moderation is precisely what the attention economy discourages. After all, if an app lets you set a healthy limit and stick to it, that’s time you’re not spending on their platform.

The key question becomes: How can we reclaim our time and attention without renouncing the digital world entirely? Some individuals take proactive steps: turning off non-essential notifications, scheduling phone-free periods, or using apps that monitor and limit social media minutes. Others are campaigning for platforms to redesign their interfaces for “time well spent” instead of mindless absorption – for instance, removing infinite scroll or making it easier to see chronological posts rather than algorithmic picks. A cultural shift is slowly happening as awareness grows. As one step, several users are heeding advice to “kill your feeds,” choosing to manually curate information sources (like using RSS readers or selecting specific news sources) so that an algorithm isn’t always choosing for them.

Feeling the pressure, tech companies have begun introducing more wellness features – like pop-up reminders that you’ve been scrolling for a while, or grayscale modes to make your screen less enticing. Still, these solutions are primarily opt-in and relatively new. We are essentially conducting a massive social experiment on ourselves, only now grappling with the cognitive fallout.

In the meantime, recognizing how deeply attention-harvesting algorithms can affect our mood and mind is an essential first step. It allows us to approach our beloved apps and platforms with more skepticism and self-regulation—treating them less like neutral windows onto the world and more like what they are: finely tuned attention traps designed to maximize time on devices. Only by acknowledging that can we begin to outsmart the algorithms, or at least resist their pull, and reclaim a bit of mental quietude in an age of constant digital noise.

The Truth

On a quiet Sunday in December 2016, a man walked into a Washington, D.C. pizzeria with a rifle, intent on investigating a bizarre conspiracy theory he had read about online. The theory – falsely claiming a child trafficking ring run by politicians in the restaurant’s basement – had proliferated on social media and been amplified by algorithms that favored its sensational narrative. There was no basement at the pizzeria, and the story was pure fabrication, yet it had gained frightening traction in the algorithmically fueled “post-truth” environment.

This incident, known as the Pizzagate conspiracy theory, was an early wake-up call that misinformation on algorithm-driven platforms isn’t just harmless chatter; it can erupt into real-world harm. Digital algorithms excel at one task above all: getting people’s attention. Unfortunately, false or misleading content often checks that box exceedingly well. Conspiracy theories, emotionally charged rumors, and clickbait headlines spread like wildfire in algorithmic feeds precisely because they spark strong reactions.

In the attention economy, virality can trump veracity, and as a result, we’ve seen a flood of misinformation.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, a deluge of false claims – from miracle cures to vaccine microchip myths – went viral on social networks. Users who engaged with one anti-vaccine video on YouTube would soon find their “Up Next” queue filled with more of the same, rapidly deepening the rabbit hole. Facebook and Twitter struggled (and often failed) to stem the tide of COVID misinformation their algorithms had helped propagate. The consequences were dire: confusion among the public, erosion of trust in health authorities, and, in some cases, people ingesting dangerous “remedies” touted in viral posts. The World Health Organization termed it an “infodemic.”2

At the heart of this problem is a harsh truth: algorithms do not distinguish between truth and lies – they distinguish between engagement and indifference. Suppose a made-up story generates lots of shares, comments, and time spent. In that case, the platform’s automated systems interpret it as valuable, engaging content, serving it to even more eyeballs.

In this way, misinformation breeds in the petri dish of algorithmic amplification. A false claim might start with a single post on a fringe site, but if it strikes a nerve and people interact with it, the recommendation engines on mainstream platforms can rapidly escalate its reach. In an echo chamber, those inclined to believe the claim will see it repeatedly, perhaps from multiple sources, giving it a veneer of legitimacy.

Meanwhile, countervailing facts often struggle to keep up – corrections don’t spread as quickly or widely because they typically provoke less engagement.

This whirlwind of online misinformation has partially undermined trust in traditional institutions – media, government, and science. When each person’s news feed is filled with different “facts,” it’s difficult to agree on a common reality. Opposing camps can form, with each side convinced the other is deluded or lying when, in fact, both are fed curated information supporting their respective beliefs. By reinforcing what each group wants to hear, the algorithms inadvertently solidify false narratives. This dynamic has contributed to what some call a “war on truth.”

Journalists and fact-checkers fight to get accurate information in front of the public. Still, they are often drowned out by the cacophony of distorted or deceptive content that simply travels faster on the rails of social media. Nowhere has this battle been more evident than in politics. Elections worldwide have seen an onslaught of fake news stories, propagated through Facebook shares or WhatsApp forwards, that sow confusion or distrust.

The sheer repetition and volume of misinformation, amplified by algorithms, can make even fantastical claims seem familiar and, thus, more believable.

The platforms are not ignorant of these issues. In recent years, companies like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter have implemented measures to combat misinformation: fact-checking labels, adjusting algorithms to down-rank debunked content, and removing egregiously false posts.

Facebook says it changed its News Feed algorithm in 2018 to prioritize content from friends and “meaningful interactions” over publisher content, partly to reduce the spread of fake news. YouTube claims it has tuned its recommendation system to limit “borderline content” (videos flirting with misinformation without outright violating policies). Twitter began flagging tweets that contained misleading information on specific topics.

These steps have shown some promise – for example, one study found that Facebook’s 2018 changes slightly reduced the overall exposure to cross-partisan misinformation. However, critics argue these efforts are too little, too late – and often applied inconsistently. Flagging or down-ranking content is a delicate task: move too aggressively, and platforms are accused of censorship or bias; move too slowly, and the damage is done.

Automated algorithms sometimes struggle to identify what is false or harmful without catching satire or legitimate debate. During fast-moving news events, by the time fact-checkers verify a piece of content, it may have already ricocheted across the globe. Moreover, determined misinformation peddlers adapt, creating new accounts or slightly altering content to evade detection. The arms race between platform moderation and disinformation peddlers continues, but many experts say the root problem lies in the algorithmic incentive structure. As long as engagement is king, sensational misinformation will have the upper hand.

Some have suggested more radical fixes: slowing down virality (for example, WhatsApp limited message forwarding after rumors led to violence in India) or changing recommendation systems to promote content from authoritative sources by default on critical topics like health and elections. Others propose that platforms be more transparent, allowing outside audits of how their algorithms might amplify false content.

“If you’re not paying for the product, you are the product.”

For the average user, living in this information war zone means we must cultivate new media literacy and skepticism skills. It’s become dangerously easy to share a provocative headline without vetting it – precisely what the algorithms count on. We may need to become our fact-checkers, pausing before reacting or reposting. The old adage, “If you’re not paying for the product, you are the product,” rings especially true here: our attention and impulses are being monetized, and truth can become collateral damage.

In the war on truth, algorithms have inadvertently armed propagandists with powerful weapons. But those same algorithms, if reoriented, could amplify truth with equal force. Imagine recommendation systems that reward accuracy and context or social feeds that expose users to a 360° view of an issue, not just the angriest take. Such visions may sound idealistic, but they are technically conceivable. The question is whether there’s the will – from both companies and users – to prioritize a healthy information ecosystem over short-term engagement metrics.

In the meantime, the battle rages on, and society is left to grapple with the consequences of a distorted reality where consensus on basic facts is increasingly elusive.

Privacy

In 2018, news broke that a political consulting firm, Cambridge Analytica, had harvested data from tens of millions of Facebook users without their explicit consent. The firm used complex algorithms to profile and target voters with tailored political ads, exploiting personal details ranging from age and interests to fears and biases. The scandal was a watershed moment, revealing how intimately our private lives can be mined and manipulated by algorithmic systems.

Yet, for all the outrage it caused, the practices at its core – pervasive data collection and automated influence – remain commonplace in the digital ecosystem. Every day, often without our awareness, our clicks, purchases, location, and even heart rate and sleep patterns are being tracked and fed into algorithms. These algorithms, in turn, make decisions or recommendations that shape our behavior. This cycle raises a fundamental question: Are we gradually surrendering our autonomy as algorithms intrude further into our private spheres?

Modern algorithms thrive on data – your data. The more they know about you, the better they can personalize content to keep you engaged or to nudge you toward a desired action (like buying a product). As a result, tech companies have built an elaborate infrastructure to monitor user activity across the web and apps. Visit a typical news website, and lurking behind the articles might be dozens of trackers logging what you read and how long you linger. In fact, the average website has about 48 different trackers that monitor visitors’ behavior and collect data.

Many of these trackers belong to third-party ad networks or analytics firms. Silicon Valley giants are at the forefront: Google’s tracking scripts are estimated to appear on 75% of the top million sites on the Internet, and Facebook’s on about 25%.3

This means that a vast portion of your online activity – even outside Google or Facebook’s own platforms – is funneled back to these companies’ algorithms, enriching the profiles they maintain on you.

What do algorithms do with this ocean of personal data? Some uses are relatively benign, even helpful – like filtering out spam emails or reminding you of an upcoming anniversary based on past calendar entries. But many uses tread into ethically fraught territory. Advertisers use algorithmic bidding systems to target ads so specifically that two people visiting the same website might see completely different advertisements tailored to their inferred interests, income level, and demographic profile.

This micro-targeting can cross the creepiness line: for example, retail algorithms infamously deduced a teenage girl was pregnant before her father did, simply by analyzing her shopping searches (leading a store to send maternity product coupons to her home). In social media, the data you unwittingly share (likes, comments, photos) trains algorithms to serve content that will trigger you emotionally – whether it’s a heartwarming memory or a post that provokes outrage. The loss of privacy here isn’t just about strangers knowing your secrets; it’s about those secrets being used to guide your hand without you realizing.

“Handing over decisions to algorithms bit by bit can lead to a subtle surrender of agency.”

Consider the subtle ways in which autonomy can be undermined. Perhaps you always thought you chose to watch that next video, but the algorithm’s suggestion led you there. Or you feel an urge to buy a particular gadget, not realizing you’ve been shown targeted ads across every site you visit for weeks.

Our online choices and increasingly offline, as algorithms filter into smart home devices, cars, and more, are often heavily nudged by algorithmic decision-making in the background. When Amazon’s algorithm decides which products to feature or a music app’s algorithmic playlist sets your mood for the day, they exercise proxy autonomy on your behalf – one that might not always align with your true interests.

Over time, we might lose the habit of choosing for ourselves, relying instead on the comfortable autopilot of algorithmic recommendations.

Privacy and autonomy are deeply connected. If you don’t know what information about you is being collected and how it’s being used, you can’t truly consent to or control the influences on your behavior. Surveillance has long been a means of control, and digital surveillance is no different. The difference now is scale and intimacy: we have invited devices into our homes and pockets that watch and listen to us.

Voice assistants like Alexa or Siri, security cameras, fitness trackers – they generate constant data flows. In authoritarian regimes, pervasive surveillance data feeds algorithms that monitor citizens’ every move. Law enforcement and governments increasingly turn to algorithms that crunch personal data – from predictive policing systems that try to forecast where crimes will occur (often reinforcing biases against marginalized neighborhoods) to social media monitoring software that flags “suspicious” activities or associations.

The boundary between public and private has blurred, with it, some measure of personal freedom. One stark example: a few years ago, investigative journalists discovered that a popular menstruation-tracking app was quietly sharing users’ intimate health data with Facebook’s analytics algorithm. Those users likely never imagined their private health details would become grist for targeted ads.

The autonomy question also extends to how algorithms constrain the choices presented to us. Imagine applying for a job and never getting a call back because an algorithmic screening tool filtered out your résumé (perhaps due to an unconscious bias in its training data). Or being denied a loan because a machine-learning model decided you were a credit risk based on correlations in your data that you’ll never know.

In these cases, an algorithm makes high-stakes decisions that profoundly affect your life, yet you often have little recourse or even knowledge that it’s happening. Privacy is violated (your data was crunched in ways you didn’t expect), and autonomy is curtailed (a decision was made for you without you). This has led to calls for a “right to explanation” in AI decisions – a principle embedded in regulations like the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) – so individuals can understand and challenge how an algorithm judges them.

One of the significant ethical challenges now is achieving informed consent in the era of big data. It’s unrealistic to expect users to read and comprehend the lengthy privacy policies of every app or site, which are often vague about algorithmic uses of data. So people click “I agree” and carry on, effectively signing away data rights by default. Some experts compare this to the early industrial era’s worker exploitation – an asymmetry of power and knowledge.

Today, tech companies hold power and knowledge (vast troves of data and sophisticated algorithms), while users are the exploited laborers, except that our data and attention are being harvested. The imbalance allows companies to keep pushing the envelope of data usage, often leaving regulators a step behind. The erosion of privacy can happen not in one fell swoop but incrementally – much like the echo chamber effect – such that we acclimate to it. A decade ago, the idea of apps constantly tracking our location or microphones passively listening might have sparked public outrage.

Now, it’s taken as a given by many. Likewise, the expectation of personal autonomy online has shifted: we tolerate that our social feed isn’t really ours but shaped by an unseen hand; we accept that search engine results or shopping suggestions are tailored based on profiling. In a sense, we trade autonomy for convenience. And to be fair, many of us find that a reasonable bargain in some instances (who wouldn’t want Google Maps to recommend the fastest route based on current traffic?).

The danger is when the trade-offs aren’t unclear or aggregate into a society-wide loss of self-determination. Can we claw back some privacy and autonomy? On the privacy front, stronger data protection laws are one path. GDPR in Europe, for instance, has forced companies to be more explicit about data collection and given users rights to access or delete their data. Some jurisdictions now mandate that companies disclose if AI algorithms are being used in decisions like hiring or lending. There’s also a burgeoning market for privacy tools – encrypted messaging, tracker-blocking browsers, VPNs – for those who want to stay off the surveillance radar.

On autonomy, user empowerment could mean building more “user-directed” technology than algorithmically driven by default. For example, offering chronological feeds as an easy option (which Twitter and Instagram eventually did after backlash to purely algorithmic feeds) or interfaces that let people actively choose categories of interest rather than having the app guess.

Ultimately, maintaining personal autonomy in a world of ubiquitous algorithms might require a cultural shift. We as users may need to become more intentional about how we interact with technology – questioning recommendations, diversifying our information sources, periodically auditing our privacy settings, and being willing to say “no” to certain convenient but invasive services. It may feel like swimming upstream, but even small acts – like denying an app permission to access your contacts or using a search engine that doesn’t track you – collectively send a message.

The technology that envelops us should operate with our explicit permission and for our benefit, not quietly erode the boundaries of selfhood. Without vigilance, we risk drifting into a future where surveillance is normalized and algorithms, not humans, subtly chart the course of individual lives. Preserving privacy and autonomy in the digital age is not just about avoiding ads or keeping secrets; it’s about defending the fundamental freedom to live and think without being constantly analyzed and guided by unseen algorithmic forces.

Work and Algorithmic Labor

In a bustling e-commerce warehouse, a picker follows the directions of an algorithm all day long. A handheld device tells her which item to grab next, the optimal path to take through the shelves, and how many seconds she has to do it. If she falls behind the algorithm’s calculated pace, she might get an automated alert – or eventually, face termination by a system that flags underperformance. There’s no human supervisor in sight; the algorithm is her boss. This scenario, already a reality in Amazon fulfillment centers and other workplaces, offers a glimpse into the broader transformation underway in the labor market. Algorithms and AI-driven automation are not just changing how we shop or socialize – they fundamentally reshape how we work, who gets employed, and what jobs might disappear or emerge.

The rise of workplace algorithms comes in a few forms. One is automation, where algorithms control machines or software that perform tasks humans used to do. Robotics on factory floors, supermarket self-checkout kiosks, and AI software that processes invoices or scans legal documents can boost productivity and displace workers. A much-cited study by economists Carl Frey and Michael Osborne in 2013 estimated that about 47% of U.S. jobs were at high risk of automation in the next couple of decades. While that specific number is debated, it’s clear that automation driven by algorithms will affect millions of jobs. A recent World Economic Forum report projected a net loss of around 14 million jobs globally over the next five years due to AI and automation – with 83 million roles eliminated and 69 million new ones created in that period.

Roles that involve routine, repetitive tasks – whether physical (like assembly line work) or cognitive (like basic bookkeeping) – are the most vulnerable. On the flip side, entirely new categories of work (data science, AI maintenance, robot technicians, etc.) are being born. Society faces the challenge of retraining and transitioning workers to these new roles, lest the benefits of algorithmic efficiency come with the pain of widespread unemployment and inequality.

Another way algorithms are changing work is through gig platforms and algorithmic management. Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, and similar gig economy apps have algorithms at their core. These platforms algorithmically dispatch tasks (a ride request, a food delivery) to gig workers, set dynamic prices, and even deactivate workers whose metrics fall short (say, an Uber driver with too low a rating might be barred by the app). This system offers flexibility but also precariousness. Workers are managed not by a human boss but by an impersonal app that can feel capricious. They often have little insight into how decisions are made – why did the algorithm send me a far-away trip, or why am I suddenly not getting any gigs tonight? It can feel like a black box controlling one’s livelihood. There have been cases where drivers were “fired” by an automatic email because the algorithm decided they were cheating the system or underperforming, and getting that decision reviewed by an actual person proved nearly impossible. This raises questions about fairness and dignity in algorithm-guided work.

Even in traditional offices, algorithms are increasingly calling the shots. Human resources departments use AI to sift through job applications, searching for keywords and patterns that predict a good hire. Some companies deploy workplace analytics that logs employees’ computer usage or track their interactions (a controversial practice, often introduced in the name of productivity). Algorithms might rank salespeople by performance data, determine bonus distributions, monitor call center employees’ tone of voice, and provide real-time feedback. In fields like finance, automated trading algorithms execute decisions faster than any human could, reshaping the role of traders. In medicine, AI diagnostic tools may guide doctors on treatment plans, potentially altering hospital workflows.

The efficiency gains from these technologies are real. Repetitive tasks, once done by humans, can be done faster and error-free by machines: a robot arm on an assembly line doesn’t tire or get injured; an AI chatbot can handle basic customer service queries 24/7. This can free humans to focus on more complex, creative, or interpersonal aspects of work – that’s the optimistic view. Historically, technology has eliminated certain jobs and created new ones (think of how the automotive industry wiped out many horse-related jobs but spawned millions of jobs in car manufacturing, maintenance, and transportation). We hope algorithms and AI will follow a similar pattern, automating drudgery and opening opportunities in fields we can’t imagine yet.

However, the transition period could be rocky. For one, the benefits of algorithm-driven automation might not be evenly distributed. There is a fear of a “winner-takes-all” economy, where those who own the AI and robotics (or have the specialized skills to work with them) capture the gains while displaced workers struggle. Imagine a warehouse where 100 workers are replaced by 10 robot technicians; those 10 may earn higher wages, but 90 jobs are gone, and not all those workers can seamlessly become robot technicians. This could exacerbate inequality and require robust social safety nets, like retraining programs or universal basic income, to ensure society benefits.

There’s also the matter of the quality of jobs. Many new algorithm-mediated jobs (like gig work) lack the security and benefits that traditional employment provides. You might have flexible hours, but no healthcare or paid leave, and income fluctuates wildly based on an algorithm’s whims or market demand. This has led to calls for updating labor laws – perhaps considering gig workers as employees or ensuring that algorithms in the workplace are audited for fairness and transparency.

On a deeper level, something is changing in the human-work relationship. The identity and satisfaction many derive from work could be challenged when machines outperform humans. If an AI can design a building, compose music, or write code more efficiently than a person, what does that mean for human architects, composers, or programmers? It may shift those professions to be more about guiding AI or focusing on high-level creative decisions and client interactions. That could be liberating – allowing humans to do what humans do best (imagination, empathy, complex strategy) and leaving routine optimization to algorithms. However, it could also be displacing if society isn’t prepared to integrate these changes.

There are some bright spots in how algorithms and humans collaborate at work. “Augmented intelligence” is a concept where AI tools assist rather than replace humans. For example, a factory worker might wear an AI-powered exosuit that helps lift heavy objects (combining human judgment with machine strength), or a doctor might use an AI that highlights suspicious areas on an MRI scan for the doctor to double-check. In journalism, algorithms can handle rote tasks like compiling market reports or sports game summaries, freeing reporters to focus on investigative pieces. Such synergy can enhance productivity and job satisfaction, letting people concentrate on tasks that require emotional intelligence or complex thought. However, ensuring that augmentation, not outright replacement, is the norm will require conscious choices by businesses and policymakers.

It’s also worth noting that some jobs will resist automation more than others. Roles that require creativity, complex manual dexterity, or deep interpersonal trust – think kindergarten teachers, senior nurses, artists, high-level engineers – are less easily handed off to machines. These may become more valued in the future. Meanwhile, entirely new industries could bloom: imagine the expansion of renewable energy tech, AI ethics consulting, virtual reality experiences, and space exploration – fields where human innovation will drive new employment.

As we stand on the cusp of what’s often called the Fourth Industrial Revolution,4 the need to proactively manage this shift is critical. Governments and educational institutions are beginning to adapt by emphasizing STEM skills and lifelong learning so that the workforce can pivot as needed. There’s also a growing movement advocating for more substantial social contracts: if algorithms and automation dramatically increase productivity (and corporate profits), perhaps some of those gains should fund public goods, like retraining programs or income support, to help workers transition.

For individuals, an actionable insight is to cultivate skills that complement AI rather than compete with it. Empathy, critical thinking, leadership, adaptability – these human traits will remain crucial. Algorithms are excellent at optimizing means to an end, but humans still define the ends. In the workplace of tomorrow, human judgment will be needed to guide where and how algorithms are deployed and ensure they align with broader goals and values beyond sheer efficiency.

In sum, the future of work in the algorithmic age holds both promise and peril. We could end up in a scenario where humans are relieved of drudgery and supported by tireless digital assistants, where work is more fulfilling and balanced. Or we could slide into a reality of high unemployment or underemployment, with a stark divide between tech-savvy knowledge workers and a displaced underclass. The outcome largely depends on the policies we set and the preparations we make now. The next chapter will be written about companies’ choices in responsibly implementing technologies, governments in cushioning the transitions, and all of us updating our skills and expectations. As with earlier technological revolutions, society will need to evolve its institutions to ensure that algorithmic labor serves humanity and not vice versa.

Social Inequality

In 2015, a shocking incident underscored how algorithmic bias can directly reflect and reinforce social inequality. A Black software engineer discovered that Google’s photo app had automatically tagged images of him and his friend (who is also Black) as “gorillas.” The outrage was immediate and justified – how could a modern AI make such a derogatory error? Google scrambled to fix the issue (ultimately removing the label “gorilla” entirely from the app’s vocabulary to prevent a repeat).

But the episode became a notorious example of racial bias in AI. The culprit was not human malice, but the training data: the algorithm had seen far more photos of gorillas and white faces than of Black faces, leading it to a grotesque misclassification. This highlighted a critical truth: algorithms inherit the biases of their creators and the data they are given. And when such biased algorithms are deployed at scale – in policing, hiring, banking, or other domains – they can perpetuate and even amplify discrimination, all under the guise of impartial technology.

Unfortunately, the Google Photos case is far from isolated. Researchers and journalists have recently uncovered many instances where algorithms produced unequal outcomes across race, gender, or other lines. For example, a 2016 investigation by ProPublica into a criminal justice algorithm called COMPAS revealed that it was nearly twice as likely to falsely label Black defendants as high risk for future crime compared to white defendants. Courts in several U.S. states used COMPAS’s risk scores to inform sentencing and parole decisions. The algorithm was supposed to bring objectivity to decisions about who might re-offend, but it appeared to exacerbate existing biases – likely because it was trained on historical crime data that already reflected policing biases (over-policing in Black communities leading to more arrests, etc.). In effect, the algorithm treated being Black as a risk factor, reinforcing systemic racism under the veneer of scientific rigor.

In another case in 2018, Amazon had to scrap an internal recruiting algorithm when they discovered it discriminated against female applicants. The AI had been trained on résumés submitted over a ten-year period, most of which came from men (reflecting the tech industry’s male dominance). The algorithm learned to favor terms more common in male candidates’ résumés, and downgrade resumes that included indicators like “women’s college” or women’s sports. Unchecked, it would have perpetuated the gender imbalance by automatically filtering out qualified women. Amazon engineers, to their credit, identified the issue in testing and discontinued use of the tool.

One shudders to think how many companies might be using similar automated filters without ever realizing the bias since many hiring algorithms are proprietary black boxes.

Even seemingly innocuous algorithms, like those governing credit scores or loan approvals, can have disparate impacts. For instance, an algorithmic model might weigh certain zip codes or income levels in ways that end up redlining minority neighborhoods (echoing the racist lending practices of the past, but now via machine). Suppose a predictive model is trained on past lending data where minorities were underserved. In that case, it may “learn” to approve fewer minority applicants, not because of creditworthiness, but because of biased precedent. AI can bake in historical inequalities without careful auditing and project them into the future.

A particularly troubling aspect is that algorithmic bias can be harder to spot than human bias. When a person is discriminatory, victims and observers can often identify it and call it out. However, it might not be obvious when a computer program is discriminatory until patterns emerge over many decisions. To the individual denied a loan or a job, it might just feel unlucky – they often have no idea an algorithm was involved, let alone how it made its decision. Moreover, algorithms can combine factors in complex ways, meaning bias might not be along a single axis like race or gender but some interaction of variables that correlates with them. This opacity makes accountability challenging.

It’s important to note that algorithms don’t intend to discriminate – they have no intentions. The bias comes from us: the data we provide (historical data reflecting societal biases), the way we frame prediction targets, and the lack of diversity or awareness in the development process. For example, facial recognition algorithms, in general, have been found to have higher error rates for people with darker skin tones and for women. In one well-known study, Gender Shades by Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru, some commercial facial recognition systems had near-perfect accuracy in identifying lighter-skinned men but error rates as high as 34% on darker-skinned women. Why? Often because the training datasets contained many more images of light-skinned males, and the algorithm never “learned” to recognize darker-skinned female faces with the same precision.

Another crucial aspect is diversity in tech. The people who design algorithms and collect training data must be diverse and culturally competent to catch biases others might overlook.

In some cases, the solution might mean saying no to algorithms altogether. For example, after learning about bias and public pushback, some major tech companies (IBM, Microsoft, Amazon) announced pauses or limits on selling facial recognition tech to police until regulations are in place. They recognized that the social risks outweighed the benefits given current limitations. Likewise, some court systems have rolled back the use of risk scores in sentencing when evidence of bias is shown.

On the flip side, if done right, algorithms could potentially help reduce human bias. Unlike humans, a well-designed algorithm can be audited and corrected when bias is found. One could train hiring algorithms on successful employees of all backgrounds and tune them to ignore demographic information, potentially catching great candidates that human recruiters (with their conscious or unconscious biases) might overlook.

AI could theoretically strip away prejudices a loan officer might harbor in lending, focusing only on objective financial indicators. There are cases in which algorithms have improved equity – for instance, a few police departments reported that using a data-driven scheduling algorithm (to decide officer deployments) reduced biased hunch-based deployments. The critical difference lies in whether the algorithm’s objective and data are aligned with fairness from the get-go.

We should also address bias in data at its root by improving the data. That means making datasets more representative and correcting historical disparities (there’s emerging research on techniques to “de-bias” training data or to deliberately include fairness constraints in machine learning models). For example, feeding a facial recognition model a balanced set of faces across races and genders can dramatically improve its balanced accuracy. Using actual clinical metrics rather than cost as a proxy avoids misleading biases in healthcare.

It’s encouraging that awareness of algorithmic bias has grown. Just a decade ago, these discussions were mostly limited to academic circles. Now, terms like “AI ethics” and “fair ML (machine learning)” are mainstream in the tech industry. Regulators are paying attention, and so are consumers – many people were horrified by stories like the Google Photos incident or the biased HR software, and they demand better. This pressure prompts companies to test and assure the public that their AI products are fair. Google, for instance, launched an AI Principles document promising not to engage in certain harmful applications and to avoid unjust bias.

Still, the journey is ongoing. Bias is a tricky foe, lurking in places designers don’t anticipate. Technology is advancing rapidly (with AI systems like deep learning neural networks that are so complex even their creators struggle to interpret how they reach decisions), ensuring fairness is a constant challenge. It may require a combination of technical solutions and strong oversight frameworks.

One can imagine in the near future something akin to an FDA for algorithms – an independent body that certifies algorithmic systems for critical uses, verifying they meet standards for bias and transparency. Public datasets could be established to benchmark AI fairness (some exist already, like diverse face databases to test face recognition). We might also see legal rights develop, such as the right to opt out of algorithmic decision-making and insist on a human review (a right enshrined in European law in some contexts).

For marginalized communities who have often borne the brunt of biased systems, the hope is that we do not simply digitize old injustices. AI should not mean “automated inequality.” Properly harnessed, algorithms could highlight inequities (data doesn’t lie if we ask the right questions) and help allocate resources more fairly.

For instance, we could identify underserved populations for healthcare outreach or optimize education resources for the schools that need them most. But that only happens if we consciously program them with equity as a goal.

In the end, algorithmic bias is a mirror of society’s biases. Addressing one means addressing the other. As we work to make algorithms fairer, we must confront the unfairness in our human institutions and data. In that way, this technological challenge is also an opportunity to correct course and ensure that our AI-driven future is more equitable than our past. The pursuit of fair algorithms reminds us that technology and society are intertwined – and that progress in one demands progress in the other.

Well

After surveying the many ways algorithms can misfire or cause harm, it’s natural to feel a bit dystopian about our digital future. However, just as these issues were made by human choices, they can be addressed by human solutions. The genie of algorithmic technology isn’t going back in the bottle – nor should it, given its tremendous benefits – so the task ahead is to build a more responsible digital future where algorithms are aligned with societal well-being.

We need a concerted effort across policy, industry, and individual action. Here are some avenues that experts and advocates are pursuing to tame the algorithmic wild west:

- Regulatory Oversight and Policy Reform: Governments worldwide are waking up to the need for rules governing algorithmic systems. In the European Union, sweeping legislation like the Digital Services Act and the proposed AI Act aim to enforce transparency and accountability for platforms and high-risk AI. These laws could require companies to disclose how their recommendation algorithms work, undergo audits for harms like misinformation or bias, and give users more control (for example, an option to turn off personalization). Antitrust actions are also on the table – by reducing the dominance of a few big tech companies, regulators hope to diminish any single algorithm’s power over the public sphere. In the U.S., discussions abound about reforming Section 230 (which shields platforms from liability for user content) to make companies more responsible for algorithmic amplification of harmful content. There’s also talk of treating certain algorithms as analogous to public utilities if they become essential gateways of information, which would subject them to stricter oversight. While regulation must be careful not to stifle innovation or free expression, wise policy can set guardrails so that profit incentives don’t consistently outweigh the public interest.

- Ethical Design and AI Governance within Industry: Forward-looking tech companies realize that baking ethics into the design process is the right thing to do and good for business (to avoid scandals and loss of user trust). This means establishing internal AI ethics teams and review boards that can veto or modify products with ethical risks. Companies like Google, Microsoft, and Facebook have published AI ethical guidelines (e.g., pledges to avoid bias, ensure privacy, allow user control, etc.), though implementation is key. Techniques like privacy-by-design (minimizing data collection, using encryption or differential privacy to protect user data) and fairness-by-design (testing algorithms on diverse scenarios and cleaning biases from data) are increasingly part of the development cycle. Some firms are even embracing “regulation simulators” – voluntarily holding their algorithms to standards that regulations would likely demand in the near future. For example, social media platforms can tweak their feed algorithms to demote blatant misinformation and clickbait, as Twitter experimented with before elections, or adjust YouTube’s recommendation AI to not rabbit-hole users into extreme content. We’ve seen that small changes in the objective function (like prioritizing quality of engagement over quantity) can significantly improve outcomes. It requires leadership that values long-term user trust over short-term engagement spikes.

- Transparency and User Empowerment: One of the simplest ways to start fixing algorithmic issues is to pull back the curtain. Suppose users know why a piece of content was shown to them (“You watched X, so we thought you’d like Y”). In that case, they are better positioned to judge its relevance and even correct the system (many platforms now allow “I’m not interested in this” feedback). Moving toward “algorithmic transparency” includes providing users access to their profile data and the inferences algorithms have made about them. Imagine if you could see that a news feed algorithm thinks you’re interested only in sports and crime. You could manually adjust those settings to include, say, arts and international news – effectively rebalancing your own feed. Some researchers suggest a concept of “nutrition labels” for algorithms, a summary that lets consumers compare how different services operate (for instance, one streaming service might clarify it focuses on popular trending videos, while another emphasizes personal viewing history). Moreover, giving users a choice of algorithms could be revolutionary. Twitter has floated the idea of letting people choose different ranking algorithms for their feed, much like one can install different browsers. A marketplace of algorithms could emerge, including nonprofit or public-service algorithms aimed at healthy information diets. At a minimum, ensuring that there’s always an option for a chronological feed or basic search sorting (as opposed to opaque ranking) can provide a baseline of neutrality when needed.

- Digital Literacy and User Habits: Technology alone can’t solve what is partly a human behavioral problem. Education is vital. Schools and communities can teach media literacy, helping people recognize how algorithms work and how to spot misinformation or manipulative content. A more informed public can actively resist the pull of echo chambers and the anxiety of the attention economy by setting personal boundaries. On an individual level, strategies might include: turning off autoplay on videos, disabling personalized ad tracking, curating friend or follow lists to ensure a variety of viewpoints, and setting time limits on social media use. Some have chosen more drastic steps like periodically “detoxing” from recommendation feeds – for example, taking a weekend to only get news from direct sources rather than via Facebook or Google’s curated picks. When widespread, these actions can push platforms to adjust. If enough users prioritize privacy or balanced content (e.g., by favoring services known for those values), market forces can compel competitors to follow suit.

- Independent Audits and Research: To truly hold algorithms accountable, independent experts need access to study them. Academics and watchdog organizations are pushing for data access provisions – letting vetted researchers examine platform data to assess algorithmic impact on things like election misinformation or teen mental health. Already, efforts like Mozilla’s YouTube Regrets project collect user reports of harmful recommendations to identify patterns. Nonprofits are developing tools to monitor how algorithms personalize search results or prices for different people, revealing potential discrimination. By supporting such research (with funding, legal protections, and public pressure on companies to cooperate), society gains a clearer picture of what’s happening under the hood, informing consumers and policymakers. In some cases, simply shining a light on a problem is enough to prompt a fix: when researchers showed evidence that Facebook’s algorithms were amplifying violence in Myanmar or that TikTok’s algorithm could lead minors to dangerous content, the companies took steps to intervene. Think of independent audits as the algorithmic equivalent of health inspections at a restaurant – a quality check for public safety.

- Human-in-the-Loop Systems: One promising design principle is keeping humans in the loop for decisions that affect people’s rights and opportunities. For instance, if an algorithm flags a job applicant as unsuitable, a human recruiter could review that decision rather than reject it outright. Some courts using risk assessment tools have mandated that judges use them as one factor among many, not as gospel. In content moderation, rather than relying purely on AI or purely on human moderators, a combination can be effective: algorithms do the first pass to remove clear-cut violations (like blatant nudity or spam), then human moderators handle the context-sensitive calls like hate speech or harassment where nuance is needed. This hybrid approach leverages the scale of algorithms and the judgment of humans. We can also require human override mechanisms – if you believe an algorithmic decision about you was wrong (your loan denial, your account ban, etc.), you should have a clear way to appeal to a human reviewer. Such safeguards ensure that algorithms serve as tools for humans, not as unchecked authorities.

- Aligning Algorithms with Public Values: A more profound, somewhat philosophical solution is realigning what algorithms optimize for. Many current problems stem from algorithms pursuing metrics like clicks, views, or profit. What if we explicitly coded values like accuracy, fairness, or user well-being into them? For example, Facebook’s AI could be tuned to maximize engagement and minimize the spread of misinformation (they’ve started doing a bit of this by demoting content flagged by fact-checkers). Recommendation systems could have multi-objective functions – balancing what you enjoy with what’s good for you, in a sense. Netflix has experimented with recommending more diverse content to users to prevent them from stagnating in one genre. Twitter engineers have found ways to identify and down-rank bot accounts to elevate authentic conversation. These are tweaks to the invisible rulebooks guiding our digital experiences. On a grander scale, some have dreamed of public interest algorithms: imagine if the library system or public broadcasters developed social media platforms where the guiding principle was civic cohesion or knowledge dissemination rather than ad revenue. They might look less glossy or grow more slowly, but they could set examples for healthier online spaces.

- Collaborative Governance and Standards: The challenges of algorithms cross borders and industries, so collaboration is key. Multistakeholder initiatives are emerging where tech companies, governments, and civil society sit together to hammer out best practices. For example, the Partnership on AI (which includes big tech firms and nonprofits) works on guidelines for fair and transparent AI. International bodies like the OECD and UNESCO have released AI ethics frameworks that countries and companies can voluntarily adopt. While these are not binding, they start to form a consensus on what responsible AI looks like. We might eventually see ISO-style technical standards for algorithmic transparency or fairness testing. Much like we have standards for quality management or environmental sustainability, algorithmic accountability standards could guide companies in certifying their products. Adhering to such standards could become a market differentiator – like a “Certified Fair AI” badge that indicates an algorithm has passed certain rigorous checks.

In truth, fixing the issues with algorithms will be a continuous process rather than a one-time feat. Technology evolves quickly – today, it’s social media feeds and credit scores; tomorrow, it might be AI tutors in education or brain-machine interfaces – and with each innovation, new ethical questions arise. But the experience we’re gaining now, grappling with social media and AI bias, is building a foundation of knowledge and tools that can be applied going forward. We’re learning how to civilize algorithms, integrating them into society’s fabric in a manner that respects human values.

It’s also heartening to remember that many of the benefits of algorithms are worth preserving. The goal isn’t to throw out personalization, recommendation engines, or AI decision-makers entirely – it’s to shape them so they enrich our lives without unintended destruction. For every harmful rabbit hole, there are countless algorithms connecting isolated individuals to the community, helping doctors spot an illness they might have missed, or making work easier and more efficient. The task is maximizing the good while mitigating the bad.

Digital citizens’ responsibilities lie in being aware, critical, and demanding of better. Some lie with the stewards of technology to be conscientious and proactive. And some lie with lawmakers and regulators to set the rules of the road. In recent years, we’ve seen a notable shift: Silicon Valley CEOs testifying in Congress, whistleblowers exposing internal algorithm issues, and tech workers themselves protesting projects they feel are unethical. The conversation has started, and that’s a powerful thing. It means society isn’t passively accepting an algorithmic fate; we’re debating it and, in many cases, pushing back.

And …

Algorithms have swiftly woven into the fabric of our daily lives, directing information flows, mediating interactions, and increasingly making decisions that once fell to humans. This unprecedented delegation of judgment to machines has brought immense convenience and capability – it’s hard to imagine navigating the modern world without the efficiency of search engines, recommendation systems, and intelligent automation.

Yet, as we have journeyed through the realms of echo chambers, attention hijacks, misinformation, privacy erosion, workplace upheaval, and encoded bias, it’s clear that our indiscriminate trust in “the algorithm” has been misplaced. These powerful tools have been shaping how we think, feel, and act in ways that often run counter to our own best interests and the health of society.

The double-edged nature of algorithms is now undeniable. On one edge, they have democratized information and customized our experiences in extraordinary ways – allowing a person in a remote village to access the same knowledge as a professor or helping a niche artist find their global audience through personalized feeds. On the other edge, they have fragmented the public square into filter bubbles of alternate realities, turbocharged the spread of falsehoods, and nudged our behaviors subtly towards whatever keeps us clicking, at times to our detriment.

They have streamlined business processes and created new wealth, but they also threaten livelihoods and raise difficult questions about what work will look like for the next generation. They promise objectivity and scale yet can perpetuate age-old biases under a glossy veneer of technology.

The societal impact of digital algorithms is thus a story of trade-offs and unintended consequences. Human cognition has been altered individually and collectively – our attention spans are shorter, and our consensus on truth is shakier. We stand more connected than ever and, paradoxically, more divided. The blame lies not in the algorithms as alien entities but in ourselves.

We built these systems, often optimizing for narrow goals like engagement or efficiency without fully considering the broader context. In a very real sense, algorithms hold up a mirror to humanity: they reflect our priorities, our data, and our flaws. When we don’t like what we see—extremist content trending or discriminatory outcomes—we are really confronting issues in our society that algorithms have amplified or unmasked.

The good news is that what humans have created, humans can change. The past few years have marked a turning point. The architects of our digital world no longer operate in naïve optimism of “connect everyone, and all will be well.” A reckoning is underway, and with it, a call to reform. Social media companies now regularly tweak their algorithms to address public concerns (even if not always transparently or adequately).

Policymakers are actively debating new laws to rein in excesses. A new generation of technologists is coming of age with an awareness of ethical design, aiming to build AI that is not only smart but also fair and aligned with human values. Users, too, are savvier – digital detox, feed curation, fact-checking, and source-vetting are becoming part of our routine, like a new form of hygiene for the information age.

However, the road ahead is long. Ensuring algorithms uplift rather than undermine society will be an ongoing balancing act. It requires vigilance: constantly monitoring outcomes, listening to those affected, and correcting course. It involves cooperation across borders and sectors since digital networks respect no geographic boundaries. And it requires a willingness to put humane principles front and center – to sometimes slow down and ask not “Can we automate this?” but “Should we, and how?”

Perhaps the most heartening insight from our exploration is that awareness is itself a remedy. The very fact that terms like “echo chamber,” “attention economy,” and “algorithmic bias” are now common parlance means the spell has been partly broken – we can see the matrix, so to speak, and are better equipped to navigate it. We can reclaim agency by deliberately seeking diverse perspectives, pausing before sharing that inflammatory post, and supporting companies and platforms that demonstrate ethical responsibility. Individually, these actions seem small, but at scale, they push the digital ecosystem in a healthier direction.

The societal impact of algorithms will not be static; it will evolve with the technology and with our responses. This is an ongoing story in which each of us – as consumers, citizens, creators, and regulators – has a role to play. The genie isn’t going back in the bottle, but maybe it doesn’t have to be a genie of chaos. With thoughtful intervention, algorithms can be more like faithful assistants: augmenting our capabilities, broadening our horizons (instead of narrowing them), and respecting our autonomy. They can help sift truth from lies if we direct them to value accuracy. They can strengthen community bonds if designed to encourage understanding over outrage. They can distribute opportunities more equitably if we demand fairness as a core success metric.

Ultimately, algorithms and society are a story of ourselves – how we choose to leverage knowledge and power. We are at a crossroads where we must decide how the next chapter will read. Will we slide into a dystopia of siloed minds and automated inequality? Or will we course-correct toward a more enlightened digital commons? The answer is being written now, not by some all-knowing code, but by collective human will.

We have the tools and understanding to create a more balanced relationship with our algorithms. The call to action is clear: we must insist on a future where technology serves humanity’s highest values rather than the other way around. In doing so, we ensure that the digital revolution ultimately contributes to a wiser, healthier, and more just society where humans remain firmly in control of our destiny, with algorithms as empowering tools, not puppet masters.

References

- Kill your Feeds - Stop letting algorithms dictate how you think (Hacker News Discussion)

- The double-edged sword of AI: Will we lose our jobs or become extremely productive?

- Social Media and Youth Mental Health [pdf]

- Gender Shades by Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru [pdf]

-

Doomscrolling or doomsurfing is the act of spending an excessive amount of time reading large quantities of news, particularly negative news, on the web and social media. It can also be defined as the excessive consumption of short-form videos or social media content for an excessive period of time without stopping. ↩

-

An infodemic is a rapid and far-reaching spread of both accurate and inaccurate information about certain issues. The word is a portmanteau of information and epidemic and is used as a metaphor to describe how misinformation and disinformation can spread like a virus from person to person and affect people like a disease. This term, originally coined in 2003 by David Rothkopf, rose to prominence in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. ↩

-

When you visit a website, you are of course observable by the site itself, but you are also observable by third-party trackers that the site embeds in its code. You might be surprised to learn that the vast majority of websites include many of these third-party trackers. Websites include them for a variety of reasons, like for advertising, analytics, and social media. ↩

-

“Fourth Industrial Revolution”, 4IR, or “Industry 4.0”, is a neologism describing rapid technological advancement in the 21st century. It follows the Third Industrial Revolution (the “Information Age”). The term was popularised in 2016 by Klaus Schwab, the World Economic Forum founder and executive chairman, who asserts that these developments represent a significant shift in industrial capitalism. ↩