Banner Ads and Pop-Ups: The First Growth Hacks

The early Internet felt like a small town. Everyone knew everyone, and the streets were lined with quirky homepages, hand-coded forums, and enough animated GIFs to make your eyes water. Then, in 1994, someone decided to hang a giant billboard in the middle of the town square. Thus, the banner ad was born.

The Banner That Started It All

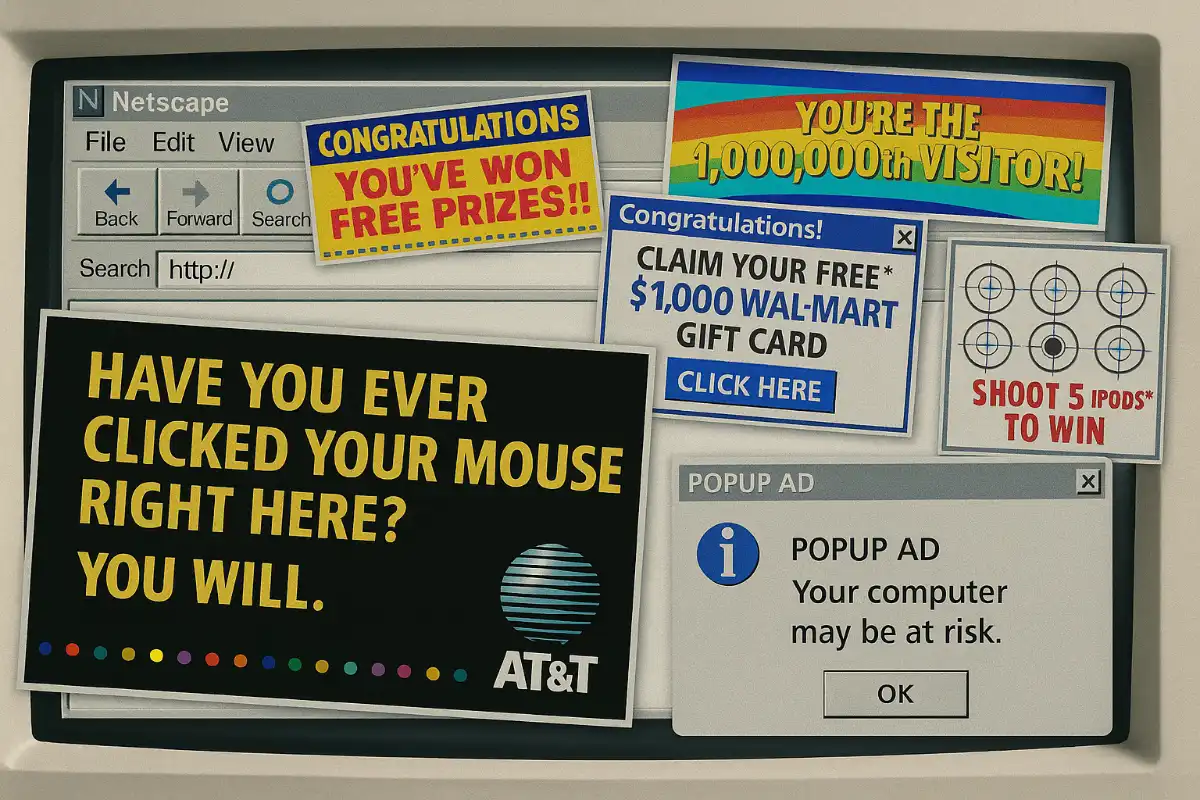

The first Banner Ad went live on HotWired, Wired magazine’s online experiment. Sponsored by AT&T, it featured a black rectangle with the words, “Have you ever clicked your mouse right here? You will.” It wasn’t clever. It wasn’t subtle. But it was effective. Nearly half of the people who saw it clicked.

To put that into perspective, today’s banner ads struggle to achieve a click-through rate of 0.1%. Back then, people clicked because it was new. The idea that an image could take you somewhere else was digital sorcery. The web was young, trust was intact, and skepticism hadn’t yet calcified into “ignore anything with flashing borders.”

That first banner did more than sell AT&T. It introduced the Internet to its first monetization model. Suddenly, the web wasn’t just a playground for academics and hobbyists. It was an ad-driven medium, primed for exploitation.

The Arrival of the Pop-Up

If banners were billboards, pop-ups were carnival barkers. They didn’t wait for you to notice them. They leapt onto your screen, interrupting your email check or your Geocities browsing session.

The culprit behind this format was Ethan Zuckerman, working at Tripod in the late 1990s. The original intent was almost noble: advertisers wanted their ads disassociated from certain content. The pop-up allowed ads to appear in their own window, floating above the site.

Zuckerman later issued a public apology in 2014, admitting that creating the pop-up was “a crime against humanity.” The Internet accepted his apology with mock forgiveness, mainly because we were still busy trying to close 17 cascading pop-ups for free ringtones. (WebArchive Archive from Aug 14, 2014)

Early Growth Hacking Before Growth Hacking Had a Name

These early ad formats weren’t just about selling. They were about pushing boundaries, testing what users would tolerate, and discovering where annoyance turned into profit. What we now call “growth hacking” was, in the 90s, just “figuring out how to get people to click before they log off AOL.”

Banner ads tested curiosity. Pop-ups tested patience. Together, they revealed that growth wasn’t always about better products—it could also be about exploiting human psychology. If enough people clicked before realizing they’d been tricked, you had scale.

The Ad Fatigue Arms Race

It didn’t take long for users to wise up. By the late 1990s, banner ads had lost their luster. Click-through rates plummeted. Pop-ups, meanwhile, escalated into pop-under windows—ads that quietly spawned beneath your browser, waiting to be discovered later like an unwelcome stowaway.

This irritation gave rise to its counter-movement: ad blockers. Once people realized they could simply make ads vanish, the relationship between users and advertisers shifted forever. Like many other normal Internet user, I Block Ads too. Every installation is a small act of protest against the idea that interruption equals innovation.

And here lies the irony: the banner ad didn’t just invent Internet advertising. It invented anti-advertising. The fatigue, distrust, and workarounds that followed became entire industries themselves.

Wild West of Ads

- The Dancing Baby Meets the Banner. In the late 90s, one of the most famous viral phenomena, the Dancing Baby, ended up on countless pages surrounded by banners. Users came for the baby, but left with a mortgage refinance ad.

- Pop-Up Hell on Napster. File-sharing sites like Napster and Kazaa weren’t just notorious for pirated music. They were also ground zero for pop-up hell. Download a track, and suddenly you’d be staring at five new browser windows, each promising miracle weight loss.

- GeoCities and the Ad Ticker. Free hosting services like GeoCities relied heavily on banner ads to subsidize free pages. Your personal shrine to “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” wasn’t really yours. It came pre-packaged with a neon-blinking side ad for low-cost travel insurance.

Startups in the Ad Economy

Looking back, banner ads and pop-ups read like a playbook of what NOT to do if you want long-term user trust. Still, their crude boldness carries lessons for today’s founders.

- Trust is finite. Early Internet users gave advertisers the benefit of the doubt. That goodwill evaporated quickly. Rebuilding trust once it has been broken is expensive, if not impossible.

- Annoyance is scalable, but so is backlash. Every pop-up installed another ad blocker. Growth built on irritation is a self-defeating loop.

- Short-term wins don’t equal innovation. Just because something gets clicks doesn’t mean it creates lasting value. The pop-up was effective, but it left a lasting legacy of resentment.

- Users adapt faster than you think. Once burned, twice shy. The rapid decline of banner effectiveness is proof that users learn quickly and defenses spread virally.

The Never-Ending Pop-Up, Rebranded

Pop-ups never really died. They evolved. Today we call them “exit-intent modals” (“Wait! Don’t leave without subscribing!”) or “cookie consent banners.” They may be dressed up in the language of UX, but the DNA is pure 90s pop-up: ambush the user before they can leave.

The lesson here isn’t that ads are evil. It’s that users are not infinitely patient test subjects. People adapt, revolt, and demand better. What started as banner ads led to the rise of Ad blockers, which in turn fueled the development of subscription models and paywalls.

The cycle repeats. Today’s equivalent might be autoplay videos or push notifications. Tomorrow, it will be something new. But the dynamic remains the same: push too hard, lose trust, and watch users flee.

Real Growth Hack

The real hack wasn’t the banner or the pop-up. It was our willingness to click. We wanted to believe the Internet was full of free prizes, miracle products, and one-millionth-visitor jackpots. Advertisers just exploited that optimism until it broke.

In hindsight, banner ads and pop-ups were less about growth and more about evolution. They forced the Internet to confront the cost of “free.” They set in motion an economy of attention, interruption, and resistance. Without them, perhaps the web would have taken longer to monetize. With them, we learned the hard way what not to trust.

And maybe that’s the final lesson: every growth hack eventually becomes a cautionary tale.