Napster, Kazaa, and the Entrepreneurial Outlaws

In the late 1990s, a dial-up modem was the gateway to forbidden treasure. You clicked “Connect,” heard that screeching handshake, and suddenly you weren’t just browsing GeoCities pages but were downloading entire discographies in the time it took to burn a frozen pizza. The names Napster and Kazaa became whispered legends in bedrooms and college dorms, sparking both awe and moral panic.

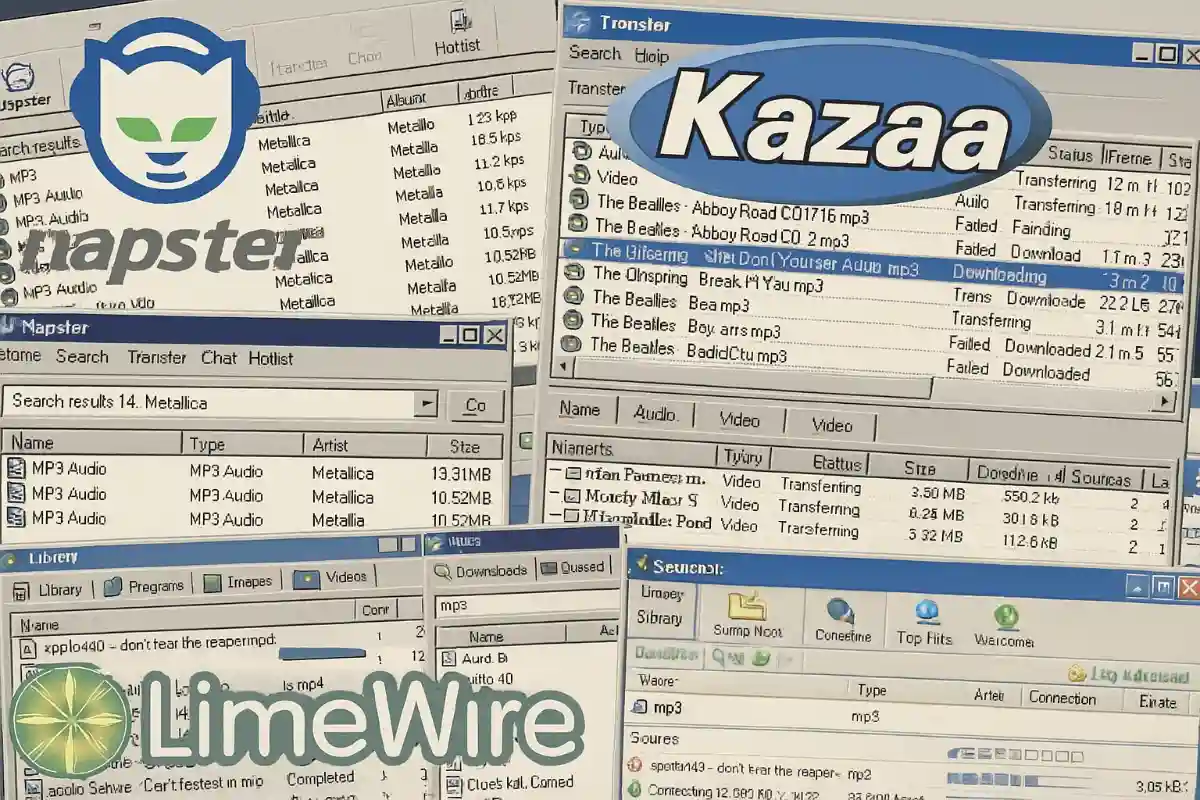

This was the peer-to-peer (P2P) revolution. It was messy, raw, and wildly illegal. But more than that, it was a generation’s first taste of disruption without permission. Long before Facebook’s motto of “move fast and break things,” these outlaw entrepreneurs had already broken the most significant industry of all: music.

The Spark: Napster

Napster launched in 1999 was the brainchild of a college dropout, Shawn Fanning, and his partner Sean Parker (later famous as Facebook’s first president). It wasn’t elegant software by today’s standards. Still, it solved a problem that seemed impossible before: how to share MP3s directly with anyone else on the Internet, without needing a central library.

“You can’t stop technology. You can’t stop music. The industry can fight all they want, but the genie is already out of the bottle.” — Shawn Fanning

Users flocked to it. In less than two years, Napster attracted over 80 million registered users at a time when the Internet itself had fewer than 400 million total. Metallica sued. The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) declared war. Universities tried to block it, fearing clogged networks.

But for teenagers sitting in bedrooms, it felt like liberation. No longer did you have to save up for a $17.99 CD at Tower Records just to hear two good tracks. With Napster, you could build a music collection overnight. It was Robin Hood in executable form.

Kazaa and the Copycats

When Napster was shut down by court order in 2001, the P2P fire didn’t die. It is simply decentralized. Kazaa, LimeWire, eDonkey2000, and countless others sprang up like mushrooms after rain.

Kazaa, developed by a pair of Estonian programmers, became infamous not only for music but for video files, the grainy, watermarked, “CAMRip” versions of Hollywood films that circulated years before Netflix would make streaming legit. Of course, Kazaa also came bundled with spyware, adware, and whatever else hitchhiked in those .exe installers. Many a Windows XP machine fell to the blue screen of death after a Kazaa binge.

It was the wild west of the Internet, where piracy and innovation blurred into one. Entrepreneurs who couldn’t get venture capital or a record deal instead shipped software out of dorm rooms and tiny European apartments. Nobody asked for permission.

The Culture of Outlaws

The P2P scene wasn’t just about free music. It rewired how people thought about digital goods. Suddenly, bits were fluid. Ownership was slippery. If you could copy it, you could share it. And if you could share it, why should you ever pay for it?

For startups, this was a lesson in viral growth. No marketing budget, no corporate endorsements, no app stores, just raw utility that spread from friend to friend. “Send me the Napster installer on ICQ.” “Burn me a copy of Kazaa on a CD-R.” It was grassroots adoption at Internet speed.

There was also the anarchist thrill. Users knew it was “wrong” in the legal sense, but it didn’t feel wrong. Record labels were the villains, charging $18 for a disc that cost cents to press. The narrative was straightforward: the scrappy hacker against the bloated industry. And in many ways, that same David versus Goliath framing still powers startups today.

Move Fast, Break Music

Mark Zuckerberg popularized the line “move fast and break things” in Facebook’s early years, but Napster lived that mantra before it had a slogan. It moved so fast it forced a multi-billion-dollar industry to its knees, and it broke not just things but entire business models.

“Most of the innovation that’s going to happen in music and media is going to come from the fringes, from people who don’t ask permission.” — Sean Parker

The lawsuits and shutdowns didn’t end the P2P era. They highlighted how fragile old structures were. The industry eventually adjusted. Apple’s iTunes and later Spotify learned from Napster’s lesson: make access cheaper, easier, and legal, or people will just keep pirating.

Napster’s fate, bankrupt by 2002, wasn’t failure. It was proof of concept. It showed that a single scrappy piece of software could topple giants, even if its creators never got to reap the rewards.

Lessons

The P2P outlaw years hold a few reminders for today’s entrepreneurs.

- Disruption starts as illegibility. At first, P2P looked like chaos, malware, and piracy. Underneath, it was an early demonstration of decentralized distribution, something we now see reborn in blockchains, torrents, and even federated AI models.

- Viral growth beats polished launches. Napster didn’t need press releases or funding. It spread because it solved a burning problem. When people want something badly enough, adoption looks like wildfire.

- Regulation is reactive, not proactive. The law didn’t anticipate P2P. By the time lawsuits arrived, the culture shift was already permanent. Today, startups in AI, fintech, and biotech face similar gaps where the product moves faster than the legal framework.

- The outlaw phase is temporary. Napster burned fast and bright, but its DNA lived on in Spotify, YouTube, and every platform that makes digital goods accessible. What begins as piracy often becomes infrastructure.

If you were online back then, you’ll remember the rituals;

- Renaming files to “Britney Spears – New Song.mp3” only to find out it was a virus.

- Queuing a 20MB file overnight, praying the dial-up wouldn’t disconnect at 99%.

- The thrill of finding a full album in 128kbps quality, hissing with artifact noise but still magic.

- The paranoia of “is the FBI watching me?” followed by the shrug of “eh, probably not.”

It wasn’t efficient, it wasn’t clean, but it was intoxicating. That spirit, the refusal to wait for permission, was what made the Internet feel alive.

Napster, Kazaa, and their peers weren’t sustainable businesses. They were flash grenades. But every Spotify playlist, every Netflix binge, every TikTok sound owes them a debt.

For founders, their story is a reminder: history didn’t begin with Silicon Valley’s slogans. The idea of “breaking things” was already running on 56k modems, written in C code by kids who wanted music. Sometimes, the entrepreneurs who burn out the fastest are the ones who light the way.